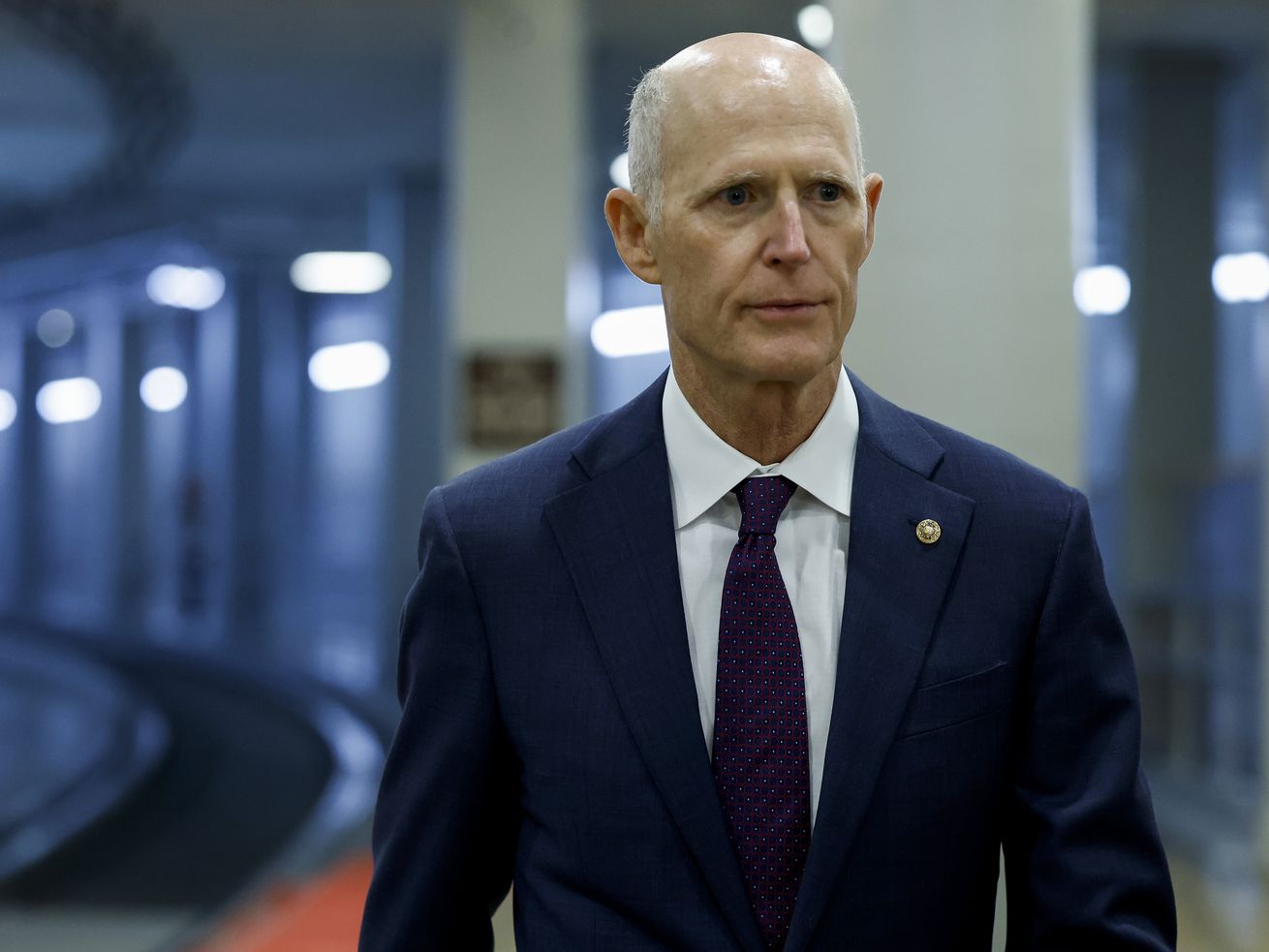

Sen. Rick Scott wants every government program — even entitlements — to expire after 5 years unless Congress approves them again.

A 12-point plan from a not particularly senior member of the US Senate is usually the kind of thing that would barely cause a ripple in the discourse. But Florida Republican Sen. Rick Scott’s plan to “rescue America,” as he puts it, was not designed to disappear quietly — and in its short life, it has already drawn a sharp rebuke during the State of the Union, sustained criticism from President Joe Biden, and even the disdain of Republican Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell.

The 10-second elevator pitch will tell you why: Scott’s proposal would radically overhaul how the federal government operates, forcing Congress to re-pass every federal law or else let them lapse — a move that, in Democrats’ telling, would endanger much of what the government does, including beloved federal programs like Medicare and Social Security.

It’s a short proposal, with little detail to flesh it out. But on its face, its meaning is plain: Every five years, every federal law would need to be passed anew in order to stay on the books.

Every federal law! During the Trump administration and the first two years of Biden’s presidency, Congress passed more than 1,000 laws every two years, to give you a sense of the scale of the task. But Biden’s critique wasn’t about the random parts of the US Code that most people don’t even know. He slammed Scott — without naming him — for trying to end Social Security and Medicare, two entitlement programs that benefit tens of millions of Americans and are enormously popular with the public.

“Instead of making the wealthy pay their fair share, some Republicans want Medicare and Social Security to sunset,” Biden said in his State of the Union address. “It is being proposed by individuals. I’m politely not naming them, but it’s being proposed by some of you.”

It was a new twist on a familiar trope: Republican proposes cutting government benefits, Democrat attacks him for it.

As CNN reported, when Scott first introduced the idea a year ago, Biden seized on it. That campaign reached a crescendo at the State of the Union speech, where Biden’s exchange with Republicans in the crowd was the standout moment for the president, leaving Democrats marveling that Scott and the GOP had “walked right into” such an obvious political trap.

By last weekend, Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell (who has a contentious relationship with Scott after the Floridian tried to oust him from leadership) was himself ripping Scott’s idea, making clear that he did not view it as a Republican idea but merely a Rick Scott idea. Scott has accused his critics of mischaracterizing his proposal, stating his support for those two programs, and hastily introduced legislation that he said would shore them up.

It was a revealing shift. Ten years ago — or 50 — this episode might have unfolded very differently. The ideological terrain has shifted after Donald Trump’s presidency, in which he won the GOP primary while promising not to cut Social Security and Medicare.

Now the party is trying to figure out its identity in a (tentative) post-Trump era. The Rick Scotts, who portray themselves as committed fiscal conservatives, want to reclaim it for small government ideology. But other Republicans aren’t as comfortable with such ideas as they used to be.

Trump changed the party’s calculus, and there might not be any going back.

A brief history of proposals to cut Medicare and Social Security

Sunset provisions, which allow laws and programs to expire unless Congress votes to continue them, came into vogue in the 1970s as a good-government proposal, the counterpart to “sunshine laws” meant to promote transparency. Sunset proposals were intended as a way to prune government programs that were inefficient or ineffective; throughout the 1970s, they were common. (Some sunset proposals at the time explicitly exempted Social Security and Medicare.) In 1975, Biden himself proposed limiting funding for existing government programs to no more than six years, an idea that the White House quickly disavowed amid the spat with Scott.

Though sunset proposals occasionally popped up in more recent years — Congress held a hearing on a sunset bill in 1998, and the libertarian Cato Institute called for sunsetting government programs in 2002 — the idea has been more or less dormant. Instead, in more recent years, Republicans targeted Social Security and Medicare specifically. President George W. Bush mounted a doomed attempt to privatize Social Security in his second term; in the early 2010s, Rep. Paul Ryan made dramatic overhauls to Social Security and Medicare part of his ambitious policy agenda.

In those days, Republicans would often defend these ideas as necessary and responsible financial stewardship. They were supposed to be the party of small government, after all. But they also faced withering and effective attacks, including during the 2012 presidential campaign, when Ryan was Mitt Romney’s vice-presidential candidate and Barack Obama called the Republican budget a plan to “end Medicare as we know it.”

Republicans have shifted on economic policy to defang Democratic attacks, but some of them want to move back

Let’s be clear: Republicans have not had some kind of come-to-Jesus moment that made them love government programs and government spending. They still propose ideas like Medicaid work requirements that would kick a lot of people off public benefits. And even for Trump, the signature policy win of his presidency was a massive tax cut for rich people and corporations, catnip for conservatives over the decades.

But they are trying to take a more measured tone on Social Security and Medicare specifically, two programs that are very important to the seniors in their base. It was a hard lesson learned from the 2012 presidential campaign, when Ryan’s budget was unpopular with seniors, and the 2016 Republican primary, in which Trump ended up steamrolling other candidates with what had been more conventional conservative views.

The problem for Republicans has always been that voters don’t want Social Security and Medicare to be cut. A 2019 Pew Research poll found that 74 percent of all Americans, including 68 percent of people who identify as Republican or lean toward that party, said no reductions should be made to Social Security benefits.

It’s a lesson that the party has finally internalized. As a showdown over raising the debt ceiling approaches, the new House Republican majority has even said that cuts to Social Security and Medicare are off the table.

That is a sharp reversal from their prior demands when a GOP House threatened to take the economy over the cliff during the Obama years. Then, Republicans in Congress and the Obama White House negotiated a deal to reduce the deficit, partly with cuts to Medicare (but not Social Security), though later Congress ended up reducing and postponing those cuts.

If you go back farther than that, McConnell himself was responsible for whipping votes in favor of George W. Bush’s plan to privatize Social Security in 2005, an episode over which he has expressed regret for their failure to pass such a bill.

But that was a lifetime ago in politics. Deficit reduction is back in vogue — it is also expected to be a focus of Biden’s proposed budget — but cutting entitlements is no longer viewed as a (politically) viable option for achieving it. Democrats certainly aren’t going to return to ideas proposed by the Obama-era Simpson-Bowles deficit reduction commission. And many Republicans no longer sound interested in major entitlement overhauls either.

All of that has made Rick Scott’s proposal a headache for Republicans and an opportunity for Democrats. That’s why, a year after he first proposed it, Scott’s critics are still talking about it.

The American financial system has long fallen short for Black communities. Crypto is just another iteration.

Crypto was sold as a sort of lifeline to Black communities, as a way to build wealth outside of the mainstream financial system that many people, understandably, mistrust. The crypto complex told the story of a potential for riches, a way for people left out of more traditional financial apparatuses to get in, bombarding the Black population with marketing and ads featuring celebrities such as LeBron James and Spike Lee. The industry made it clear: If you didn’t get in, well, you might just be missing out. Many Black investors picked up what marketers were putting down, investing in cryptocurrency at higher rates than their white counterparts — especially Black investors under 40.

Now, cryptocurrencies are trading well below their 2021 highs. Many NFTs have plummeted in value and are essentially worthless. Some high-profile projects and companies in the space have imploded, and it’s not clear what, if anything, customers who put their money into those entities will get back. All is not totally lost. Investors who got into cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin and ethereum in the early days are still ahead (assuming they haven’t lost the coins or had them scammed away). Crypto often goes through boom and bust cycles, and it’s unlikely the ecosystem is dead.

Still, Black investors were not generally among that early group to dive into crypto, as the Atlantic’s Annie Lowrey notes. Instead, many of them got in late, and some appear to have bought high and sold low. According to a recent LendingTree survey, Black crypto investors were likelier than white crypto investors to say that they had borrowed money to make their investment and that they had sold their crypto for less than it was worth. In other words, some Black investors have been left holding the bag.

“The idea that crypto is somehow providing an avenue that’s easier than other forms doesn’t pan out. It’s not as democratizing and welcoming as suggested,” said Algernon Austin, director of race and economic justice at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, who has spoken out in the past about the risks of crypto to Black communities. “The crypto industry is concerned about the crypto industry, it’s not concerned about Black wealth.”

It’s a familiar tale throughout America’s history, explained Mehrsa Baradaran, a law professor at the University of California Irvine and author of multiple books on financial inequality and the racial wealth gap. She drew parallels to housing contract sales offered to Black communities in the wake of the New Deal in the 1950s and ’60s and to subprime home loans prior to the global financial crisis disproportionately made to communities of color. In both instances, Black consumers were targeted with predatory financial products existing somewhat on the margins.

Most notably, she pointed to the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, more colloquially known as the Freedman’s Bank, a private savings bank established by Congress in the wake of the Civil War meant to help formerly enslaved people establish financial stability. The endeavor lasted for nine years and ended in disaster — its funds were mishandled, and eventually, the bank collapsed. Many depositors never saw their money again.

“You have the perfect conditions that led to the Freedman’s Bank, that led to the subprime crisis, that led to the contract sales after the New Deal, which is that capitalism is undergoing some shift and something is wrong and the government needs to handle it, but instead, they leave out certain people and then some terrible, exploitative incentive gets born, and someone is always going to step into that,” Baradaran said.

In the 19th century, that took the shape of a bank that squandered Black people’s money and sowed skepticism of the financial system that persists today. In the 21st century, it was a pitch to build wealth through a new, largely unregulated technology that would later see the bottom substantially fall out. “It is a looting of people’s money,” Baradaran said.

To back up a bit — or, rather, a lot, to after the Civil War — the US Congress established the Freedman’s Bank in 1865. It was meant to serve as a savings institution for formerly enslaved people and their families, and deposits were supposed to be invested in “stocks, bonds, Treasury notes, or other securities of the United States.” Other loans weren’t initially intended to be made.

As Baradaran explained in her 2017 book, The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap, a bank wasn’t exactly an ideal solution — giving formerly enslaved people land would have been better. “Blacks had not asked for the bank, but land grants having been foreclosed on by violence and southern retrenchment, the bank was a stand-in,” she wrote. “The reformers promised the Black community that the bank was the preferred and proper means by which they would achieve land ownership on their own.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24433134/GettyImages_1455814406.jpg) Frances Benjamin Johnson/Library of Congress/Getty Images

Frances Benjamin Johnson/Library of Congress/Getty Images

The Freedman’s Bank opened in New York in April of 1865 and over the course of a few years built up 19 branches. Eventually, the bank hit 37 branches and had tens of thousands of depositors. People were allowed to open accounts with as little as 5 cents, and most deposits were under $60. The bank struggled financially, and in 1867, its headquarters were moved to Washington, DC, and a new group of bankers, politicians, and businessmen took the wheel. Congress changed the bank’s charter to let the people now running the show invest in real estate and railroads, and they started to make risky bets. When financial panic hit in 1873, it took an enormous toll on the Freedman’s Bank, and the value of its investments plunged. There was a run on several branches, meaning many depositors tried to get their money out all at once, and by the time Congress sent regulators to take a look under the hood at what was going on, it was largely too late.

In 1874, abolitionist and writer Frederick Douglass was brought in to run the bank, but he quickly realized it was “the black man’s cow, but the white man’s milk.” Less than two months later, he described the situation as being “married to a corpse” and recommended Congress shutter the bank, which it did in June of that year. The bank’s assets were not backed by the federal government — a fact many customers had not realized — and many customers’ deposits were gone.

In The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote that “not even ten additional years of slavery could have done so much to throttle the thrift of the freedmen as the mismanagement and bankruptcy of the series of savings banks chartered by the Nation for their special aid.”

“What should have happened in 1865 is that the treasonous Southerners should have lost their land because they had fought for the right to maintain slavery, and the people who for hundreds of years had grown the land should have gotten it,” Baradaran said in an interview. Instead, they got a poorly run bank, their money was squandered on irresponsible investments, and they were left with nothing.

The incident contributed to an ongoing mistrust of banks among Black communities. And in the modern day, it’s also hard not to see the parallels between the Freedman’s Bank and the most recent crypto implosion, where once again upstart institutions meant to be a new avenue for people to build wealth have gone bottoms-up or, at the very least, are teetering. “This is what you see with bitcoin, you get the scammers and the hucksters and the fraud, people who come in and say, ‘Look, we’re going to exploit people’s genuine desire to build wealth in a fucked-up system,’” Baradaran said.

When the mainstream system doesn’t work — and it really doesn’t for many Black Americans — it’s natural to look elsewhere for something that does. That’s where the appeal of something like crypto resides. People are told it’s a way to establish financial independence and freedom and get away from the institutions that have wronged them in the past. It’s a prospect that’s easy to want to believe in.

“It’s important to recognize that the Black population has more economic hardship and economic insecurity than the white population or the US population overall on average. You have more poverty, higher rates of debt, higher rates of insecurity, unstable work hours, unaffordable housing, there are a number of financial stresses in the lives of many African Americans,” Austin said. “So when you’re worrying how you’re going to pay your bills regularly and how you’re going to get ahead and someone shows up and says, ‘I have the solution, and this will help you pay all your bills and help you pay your kids’ college and the house that you’ve always dreamed about,’ that’s pretty enticing.”

Charlotte Principato, financial services analyst at polling firm Morning Consult, said Black Americans “show through their higher ownership of cryptocurrency than adults of other races or ethnicities that they are open to alternative forms of payment and investment outside the sphere of traditional finance” and that it’s “not surprising” that they’re interested in alternative assets given that the mainstream system has not served them well. “It makes sense that they would try to stake their claim and find success,” she said. “It is unfortunate that it is that way with such a speculative asset.”

In conversations with crypto proponents over the years, I’ve heard time and time again that it is specifically good for communities of color, that it’s solving a problem for the unbanked, meaning people without banking access, and the underbanked, people who have banking accounts but often rely on other financial services, such as payday loans and check-cashing services, in the day to day.

It’s an argument that’s nice to believe. It’s also one that often falls apart: With potential upside risk comes a lot of the downside risk we’re seeing today.

For one thing, it’s rare to hear people who work on financial inclusion more broadly offer up crypto as a solution. They’re much likelier to push for postal banking and public banking and advocate for more credit unions. It’s hard to see how a hyper-capitalist, unregulated system would avoid the mistakes our already-capitalist, sometimes lightly regulated system already entails. And to state the obvious here, the crypto industry is here to make money. Businesses in the space aren’t generally doing business out of the goodness of their hearts.

“The marketing campaign is not out of generosity or philanthropy, that’s the business model, the business model requires getting as many people as possible so then prices go up,” Austin said. “It’s not an investment that’s built on providing any goods or service, so once you understand that, you understand you’re really resting on herd mentality, only then you have to go with the herd and then make sure to jump away before it goes off the cliff.”

Many investors — including many Black investors — did not jump away soon enough.

To be sure, the crypto industry has not completely imploded, though many big names in the arena have. There are plenty of people who still say they believe it is an avenue for building wealth. Charlene Fadirepo, a regulator turned bitcoin activist, told me she thinks the 2022 market crash was an “incredible teachable moment” for crypto investors to become safe, smart, and confident. “To be honest, traditional banking doesn’t have a great track record dealing with Black consumers,” she said, an assertion that is hard to dispute. She still believes bitcoin, specifically, has an appeal in offering “financial autonomy,” though she’s somewhat dubious of other cryptocurrencies. “There are fundamentals that promote bitcoin as a long-term investment … that is not the case for all cryptocurrencies,” she said.

Fadirepo recalled a recent class she was teaching on crypto in South Carolina where a Black woman in the class said she had lost $3,000 when Celsius, a now-bankrupt crypto lender, failed. The woman didn’t want people to feel bad for her, Fadirepo said, but wanted people to realize they need to protect their crypto by storing it in a “cold storage wallet,” meaning not on a third-party platform and not connected to the internet. “I could have talked for hours, but that one anecdote shifted the conversation in the room,” she said. “I see a bright side here, and that bright side is just encouraging a level of investor discipline and a real need to be informed.”

That people sometimes just need to learn lessons from their mistakes is something you hear often in investing; there’s a line of thought that loss is sometimes just an opportunity to do better moving forward. While often delivered with the best of intentions, the sentiment can feel hollow. Many times, investors aren’t clear on the rules of the game they’re playing, and the people they’re playing against — or the people who are running the game — aren’t forthcoming about what’s going on in the background. Placing the blame on the losers, especially when they’re set up to lose, happens time and time again.

“It’s the double whammy of not only is your money stolen, but as far as anyone knows, it’s your fault, you should have known better,” Baradaran said. “It’s shocking how similar those arguments end up.”

There’s no denying the American financial system is in many ways stacked against Black investors and consumers. And the best way to address that might be to try to fix the system instead of creating new avenues or endeavors, whether the Freedman’s Bank or some crypto project, which have many of the same failings but without the guardrails.

“If the system’s broken, let’s fix it, instead of saying, ‘Look, the system’s broken, let’s create this other system,’” Baradaran said, comparing it to deciding to go live on Mars because Earth is too screwed up. “It’s losing all the lessons that we had to learn the hard way in this financial system, which is that you need trust, you have to have trust. And if we allow fraud without regulation, there will always be fraud.”

Fraud and mistrust are what have led many Black consumers to faulty offers and products over and over again. The latest iteration is crypto, but it probably won’t be the last.

Gonzalez v. Google and Twitter v. Taamneh seek to conscript big tech into the war on terror; the results could be disastrous.

In 2015, individuals affiliated with the terrorist group ISIS conducted a wave of violence and mass murder in Paris — killing 129 people. One of them was Nohemi Gonzalez, a 23-year-old American student who died after ISIS assailants opened fire on the café where she and her friends were eating dinner.

A little more than a year later, on New Year’s Day 2017, a gunman opened fire inside a nightclub in Istanbul, killing 39 people — including a Jordanian national named Nawras Alassaf who has several American relatives. ISIS also claimed responsibility for this act of mass murder.

In response to these horrific acts, Gonzalez’s and Alassaf’s families brought federal lawsuits pinning the blame for these attacks on some very unlikely defendants. In Gonzalez v. Google, Gonzalez’s survivors claim that the tech giant Google should compensate them for the loss of their loved one. In a separate suit, Twitter v. Taamneh, Alassaf’s relatives make similar claims against Google, Twitter, and Facebook.

The thrust of both lawsuits is that websites like Twitter, Facebook, or Google-owned YouTube are legally responsible for the two ISIS killings because ISIS was able to post recruitment videos and other content on these websites that were not immediately taken down. The plaintiffs in both suits rely on a federal law that allows “any national of the United States” who is injured by an act of international terrorism to sue anyone who “aids and abets, by knowingly providing substantial assistance” to anyone who commits “such an act of international terrorism.”

The stakes in Gonzalez and Twitter are enormous. And the possibility of serious disruption is fairly high. There are a number of entirely plausible legal arguments, which have been embraced by some of the leading minds on the lower federal courts, that endanger much of the modern-day internet’s ability to function.

It’s not immediately clear that these tech companies are capable of sniffing out everyone associated with ISIS who uses their websites — although they claim to try to track down at least some ISIS members. Twitter, for example, says that it has “terminated over 1.7 million accounts” for violating its policies forbidding content promoting terrorism or other illegal activities.

But if the Court decides they should be legally responsible for removing every last bit of content from terrorists, that opens them up to massive liability. Federal antiterrorism law provides that a plaintiff who successfully shows that a company knowingly provided “substantial assistance” to a terrorist act “shall recover threefold the damages he or she sustains and the cost of the suit.” So even an enormous company like Google could face the kind of liability that could endanger the entire company if these lawsuits prevail.

A second possibility is that these companies, faced with such extraordinary liability, would instead choose to censor millions of peaceful social media users in order to make sure that no terrorism-related content slips through. As a group of civil liberties organizations led by the Center for Democracy and Technology warn in an amicus brief, an overbroad reading of federal antiterrorism law “would effectively require platforms to sharply limit the content they allow users to post, lest courts find they failed to take sufficiently ‘meaningful steps’ against speech later deemed beneficial to an organization labeled ‘terrorist.’”

And then there’s a third possibility: What if a company like Google, which may be the most sophisticated data-gathering institution that has ever existed, is actually capable of building an algorithm that can sniff out users who are involved in illegal activity? Such technology might allow tech companies to find ISIS members and kick them off their platforms. But, once such technology exists, it’s not hard to imagine how authoritarian world leaders would try to commandeer it.

Imagine a world, for example, where India’s Hindu nationalist prime minister Narendra Modi can require Google to turn such a surveillance apparatus against peaceful Muslim political activists as a condition of doing business in India.

And there’s also one other reason to gaze upon the Gonzalez and Twitter cases with alarm. Both cases implicate Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, arguably the most important statute in the internet’s entire history.

Section 230 prohibits lawsuits against websites that host content produced by third parties — so, for example, if I post a defamatory tweet that falsely accuses singer Harry Styles of leading a secretive, Illuminati-like cartel that seeks to overthrow the government of Ecuador, Styles can sue me for defamation but he cannot sue Twitter. Without these legal protections, it is unlikely that interactive websites like Facebook, YouTube, or Twitter could exist. (To be clear, I am emphatically not accusing Styles of leading such a cartel. Please don’t sue me, Harry.)

But Section 230 is also a very old law, written at a time when the internet looked very different than it does today. It plausibly can be read to allow a site like YouTube or Twitter to be sued if its algorithm surfaces content that is defamatory or worse.

There are very serious arguments that these algorithms, which, at least in some cases, can surface more and more extreme versions of the content users like to watch, eventually leading them to some very dark places, play a considerable role in radicalizing people on the fringes of society. In an ideal world, Congress would wrestle with the nuanced and complicated questions presented by these cases — such as whether we should tolerate more extremism as the price of universal access to innovation.

But the likelihood that the current Congress will be able to confront these questions in any serious way is, to put it mildly, not high. And that means that the Supreme Court will almost certainly move first, potentially stripping away the legal protections that companies like Google, Facebook, or Twitter need to remain viable businesses — or, worse, forcing these companies to engage in mass censorship or surveillance.

Indeed, one reason why the Gonzalez and Twitter cases are so disturbing is that they turn on older statutes and venerable legal doctrines that were not created with the modern-day internet in mind. There are very plausible, if by no means airtight, arguments that these outdated US laws really do impose massive liability on companies like Google for the actions of a mass murderer in Istanbul.

The Gonzalez case, explained

The question the Supreme Court is supposed to resolve in the Gonzalez case is whether Section 230 immunizes tech companies like Google or Facebook from liability if ISIS posts recruitment videos or other terrorism-promoting content to their websites — and then that content is presented to website users by the website’s algorithm. Before we can analyze this case, however, it is helpful to understand why Section 230 exists, and what it does.

Section 230 is the reason why the modern internet can exist

Before the internet, companies that allow people to communicate with each other typically were not legally responsible for the things those people say to one another. If I call up my brother on the telephone and make a false and defamatory claim about Harry Styles, for example, Styles may be able to sue me for slander. But he couldn’t sue the phone company.

The rule is different for newspapers, magazines, or other institutions that carefully curate which content they publish. If I publish the same defamatory claim on Vox, Styles may sue Vox Media for libel.

Much of the internet, however, exists in a gray zone between telephone companies, which do not screen the content of people’s calls, and curated media like a magazine or newspaper. Websites like YouTube or Facebook typically have terms of service that prohibit certain kinds of content, such as content promoting terrorism. And they sometimes ban or suspend certain users, including former President Donald Trump, who violate these policies. But they also don’t exercise anywhere near the level of control that a newspaper or magazine exercises over its content.

This uncertainty about how to classify interactive websites came to a head after a 1995 New York state court decision ruled that Prodigy, an early online discussion website, was legally responsible for anything anyone posted on its “bulletin boards” because it conducted some content moderation.

Which brings us to Section 230. Congress enacted this law to provide a liability shield to websites that publish content by the general public, and that also employ moderators or algorithms to remove offensive or otherwise undesirable content.

Broadly speaking, Section 230 does two things. First, it provides that “no provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” This means that if a website like YouTube or Facebook hosts content produced by third parties, it won’t be held legally responsible for that content in the same way that a newspaper is responsible for any article published in its pages.

Second, Section 230 allows online forums to keep their lawsuit immunity even if they “restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable.” This allows these websites to delete content that is offensive (such as racial slurs or pornography), that is dangerous (such as content promoting terrorism), or that is even just annoying (such as a bulletin board user who continuously posts the word “BABABOOEY” to disrupt an ongoing conversation) without opening the website up to liability.

Without these two protections, it is very unlikely that the modern-day internet would exist. It simply is not possible for a social media site with hundreds of millions of users to screen every single piece of content posted to those websites to make sure that it is not defamatory — or otherwise illegal. As the investigative journalism site ProPublica once put it, with only a mild amount of hyperbole, the provision of Section 230 protecting interactive websites from liability is the “twenty-six words [that] created the internet.”

The Gonzalez plaintiffs make a plausible argument that they’ve found a massive loophole in Section 230

The gist of the plaintiffs’ arguments in Gonzalez is that a website like YouTube or Facebook is not protected by Section 230 if it “affirmatively recommends other party materials,” regardless of whether those recommendations are made by a human or by a computer algorithm.

Thus, under this theory, while Section 230 prohibits Google from being sued simply because YouTube hosts an ISIS recruitment video, its Section 230 protections evaporate the minute that YouTube’s algorithm recommends such a video to users.

The potential implications of this legal theory are fairly breathtaking, as websites like Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook all rely on algorithms to help their users sort through the torrent of information on those websites. Google’s search engine, moreover, is basically just one big recommendation algorithm that decides which links are relevant to a user’s query, and which order to list those links in.

Thus, if Google loses its Section 230 protections because it uses algorithms to recommend content to users, one of the most important backbones of the internet could face ruinous liability. If a news outlet that is completely unaffiliated with Google publishes a defamatory article, and Google’s search algorithm surfaces that article to one of Google’s users, Google could potentially be liable for defamation.

And yet, the question of whether Section 230 applies to websites that use algorithms to sort through content is genuinely unclear, and has divided lower court judges who typically approach the law in similar ways.

In the Gonzalez case itself, a divided panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit concluded that algorithms like the one YouTube uses to display content are protected by Section 230. Among other things, the majority opinion by Judge Morgan Christen, an Obama appointee, argued that websites necessarily must make decisions that elevate some content while rendering other content less visible. Quoting from a similar Second Circuit case, Christen explained that “websites ‘have always decided … where on their sites … particular third-party content should reside and to whom it should be shown.’”

Meanwhile, the leading criticism of Judge Christen’s reading of Section 230 was offered by the late Judge Robert Katzmann, a highly regarded Clinton appointee to the Second Circuit. Dissenting in Force v. Facebook (2019), Katzmann pointed to the fact that Section 230 only prohibits courts from treating an online forum “as the publisher” of illegal content posted by one of its users.

Facebook’s algorithms do “more than just publishing content,” Katzmann argued. Their function is “proactively creating networks of people” by suggesting individuals and groups that the user should attend to or follow. That goes beyond publishing, and therefore, according to Katzmann, falls outside of Section 230’s protections.

The likely reason for this confusion about what Section 230 means is that the law was enacted nearly three decades ago, when the internet as a mass consumer phenomenon was still in its infancy. Congress did not anticipate the role that algorithms would play in the modern-day internet, so it did not write a statute that answers the question of whether algorithms that recommend content to website users shatter Section 230 immunity with clarity. Both Christen and Katzmann offer plausible readings of the statute.

In an ideal world, Congress would step in to write a new law that strikes a balance between ensuring that essential websites like Google can function, while potentially including some additional safeguards against the promotion of illegal content. But the House of Representatives just spent an entire week trying to figure out how to elect a speaker, so the likelihood that the current, highly dysfunctional Congress will perform such a nuanced and highly technical task is vanishingly small.

And that means that the question of whether much of the internet will continue to function will turn on how nine lawyers in black robes decide to read Section 230.

The Twitter case, explained

Let’s assume for a moment that the Supreme Court accepts the Gonzalez plaintiffs’ interpretation of Section 230, and thus Google, Twitter, and Facebook lose their immunity from lawsuits claiming that they are liable for the ISIS attacks in Paris and Istanbul. To prevail, the plaintiffs in both Gonzalez and Twitter would still need to prove that these websites violated federal antiterrorism law, which makes it illegal to “knowingly” provide “substantial assistance” to “an act of international terrorism.”

The Supreme Court will consider what this statute means when it hears the Twitter case. But this statute is, to say the least, exceedingly vague. Just how much “assistance” must someone provide to a terroristic plot before that assistance becomes “substantial?” Is it enough for the Twitter plaintiffs to show that a tech company provided generalized assistance to ISIS, such as by operating a website where ISIS was able to post content? Or do those plaintiffs have to show that, by enabling ISIS to post this content online, these tech companies specifically provided assistance to the Istanbul attack itself?

The Twitter plaintiffs would read this antiterrorism statute very broadly

The Twitter plaintiffs’ theory of what constitutes “substantial assistance” is quite broad. They do not allege that Google, Facebook, or Twitter specifically set out to assist the Istanbul attack itself. Rather, they argue that these websites’ algorithms “recommended and disseminated a large volume of written and video terrorist material created by ISIS,” and that providing such a forum for ISIS content was key to “ISIS’s efforts to recruit terrorists, raise money, and terrorize the public.”

Perhaps that is true, but it’s worth noting that Twitter, Facebook, or Google are not accused of providing any special assistance to ISIS. Indeed, all three companies say that they have policies prohibiting content that seeks to promote terrorism, although ISIS was sometimes able to thwart these policies. Rather, as the Biden administration says in an amicus brief urging the justices to rule in favor of the social media companies, the Twitter plaintiffs “allege that defendants knew that ISIS and its affiliates used defendants’ widely available social media platforms, in common with millions, if not billions, of other people around the world, and that defendants failed to actively monitor for and stop such use.”

If a company can be held liable for a terrorist organization’s actions simply because it allowed that organization’s members to use its products on the same terms as any other consumer, then the implications could be astonishing.

Suppose, for example, that Verizon, the cell phone company, knows that a terrorist organization sometimes uses Verizon’s cellular network because the government occasionally approaches Verizon with wiretap requests. Under the Twitter plaintiffs’ reading of the antiterrorism statute, Verizon could potentially be held liable for terrorist attacks committed by this organization unless it takes affirmative steps to prevent that organization from using Verizon’s phones.

Faced with the threat of such awesome liability, these companies would likely implement policies that would harm millions of non-terrorist consumers. As the civil liberties groups warn in their amicus brief, media companies are likely to “take extreme and speech-chilling steps to insulate themselves from potential liability,” cutting off communications by all kinds of peaceful and law-abiding individuals.

Or, worse, tech companies might try to implement a kind of panopticon, whereby every phone conversation, every email, every social media post, and every direct message is monitored by an algorithm intended to sniff out terrorist sympathizers — and then deny service to anyone who is flagged by this algorithm. And once such a surveillance network is built, authoritarian rulers across the globe are likely to pressure these tech companies to use that network to target political dissidents and other peaceful actors.

There is an easy way for the Supreme Court to avoid these consequences in the Twitter case

Despite all of these concerns, the likely reason why the Twitter case had enough legs to make it to the Supreme Court is that the relevant antiterrorism law is quite vague, and court decisions do little to clarify the law. That said, one particularly important federal court decision provides the justices with an off-ramp they can use to dispose of this case without making Google responsible for every evil act committed by ISIS.

Federal law states that, in determining whether an organization provided substantial assistance to an act of international terrorism, courts should look at “the decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in Halberstam v. Welch,” a 1983 decision that, in Congress’s opinion, “provides the proper legal framework for how such liability should function.”

The facts of Halberstam could not possibly be more dissimilar than the allegations against Google, Twitter, and Facebook. The case concerned an unmarried couple, Linda Hamilton and Bernard Welch, who lived together and who grew fantastically rich due to Welch’s five-year campaign of burglaries. Welch would frequently break into people’s homes, steal items made of precious metals, melt them into bars using a smelting furnace installed in the couple’s garage, and then sell the precious metals. Hamilton, meanwhile, did much of the paperwork and bookkeeping for this operation, but did not actually participate in the break-ins.

The court in Halberstam concluded that Hamilton provided “substantial assistance” to Welch’s criminal activities, and thus could be held liable to his victims. In so holding, the DC Circuit also surveyed several other cases where courts concluded that an individual could be held liable because they provided substantial assistance to the illegal actions of another person.

In some of these cases, a third-party egged on an individual who was engaged in illegal activity — such as one case where a bystander yelled at an assailant who was beating another person to “kill him” and “hit him more.” In another case, a student was injured by a group of students who were throwing erasers at each other in a classroom. The court held that a student who threw no erasers, but who “had only aided the throwers by retrieving and handing erasers to them” was legally responsible for this injury too.

In yet another case, four boys broke into a church to steal soft drinks. During the break-in, two of the boys carried torches that started a fire that damaged the church. The court held that a third boy, who participated in the break-in but did not carry a torch, could still be held liable for the fire.

One factor that unifies all of these cases is that the person who provided “substantial assistance” to an illegal activity had some special relationship with the perpetrator of that activity that went beyond providing a service to the public at large. Hamilton provided clerical services to Welch that she did not provide to the general public. A bystander egged on a single assailant. A student handed erasers to specific classmates. Four boys decided to work together to burglarize a church.

The Supreme Court, in other words, could seize upon this unifying thread among these cases to rule that, in order to provide “substantial assistance” to a terrorist act, a company must have some special relationship with that organization that goes beyond providing it a product on the same terms that the product is available to any other consumer. This is more or less the same approach that the Biden administration urges the Court to adopt in its amicus brief.

Again, the most likely reason why this case is before the Supreme Court is because previous court decisions do not adequately define what it means to provide “substantial assistance” to a terrorist act, so neither party can produce a slam-dunk case which definitely tells the justices to rule in their favor. But Halberstam and related cases can very plausibly be read to require companies to do more than provide a product to the general public before they can be held responsible for the murderous actions of a terrorist group.

Given potentially disastrous consequences for all internet commerce if the Court rules otherwise, that’s as good a reason as any to read this antiterrorism statute narrowly. That would, at least, neutralize one threat to the modern-day internet — although the Court could still create considerable chaos by reading Section 230 narrowly in the Gonzalez case.

There are legitimate reasons to worry about social media algorithms, even if these plaintiffs should not prevail

In closing this long and complicated analysis of two devilishly difficult Supreme Court cases, I want to acknowledge the very real evidence that the algorithms social media websites use to surface content to their users can cause significant harm. As sociologist and Columbia professor Zeynep Tufekci wrote in 2018, YouTube “may be one of the most powerful radicalizing instruments of the 21st century” because of its algorithms’ propensity to serve up more and more extreme versions of the content its users decide to watch. A casual runner who starts off watching videos about jogging may be directed to videos about ultramarathons. Meanwhile, someone watching Trump rallies may be pointed to “white supremacist rants.”

If the United States had a more functional Congress, then there may very well be legitimate reasons for lawmakers to think about amending Section 230 or the antiterrorism law at the heart of the Twitter case to quell this kind of radicalization — though obviously such a law would need to comply with the First Amendment.

But the likelihood that nine lawyers in black robes, none of whom have any particular expertise on tech policy, will find the solution to this vexing problem in vague statutes that were not written with the modern-day internet in mind is small, to say the least. It is much more likely that, if they rule against the social media defendants in this case, the justices will suppress internet commerce across the globe, that they will diminish much of the internet’s ability to function, and that they may do something even worse — effectively forcing companies like Google to become engines of censorship or mass surveillance.

Indeed, if the Court interprets Section 230 too narrowly, or if it reads the antiterrorism statute too broadly, that could effectively impose the death penalty on many websites that make up the backbone of the internet. That would be a monumental decision, and it should come from a body with more democratic legitimacy than the nine unelected people who make up the Supreme Court.